When the British artist David Hockney takes photographs, he sometimes pulls them together into a collage. He calls this “drawing with a camera.”

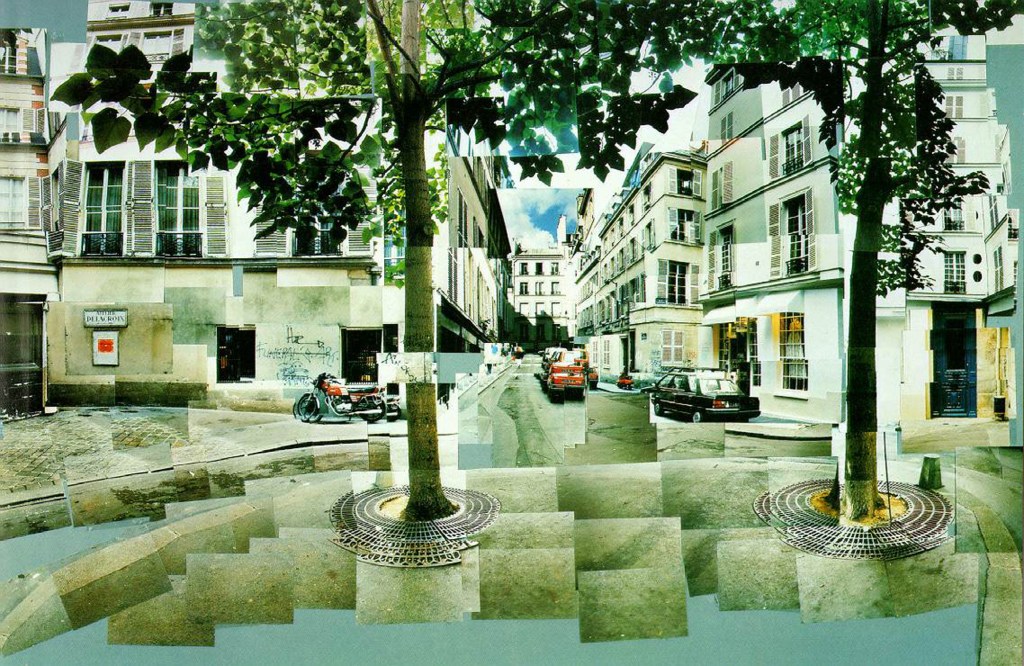

This is one such collage. It’s called Place Furstenberg, Paris, August 7,8,9, 1985 #1.

This is another one. It’s called The Desk, July 1st 1984.

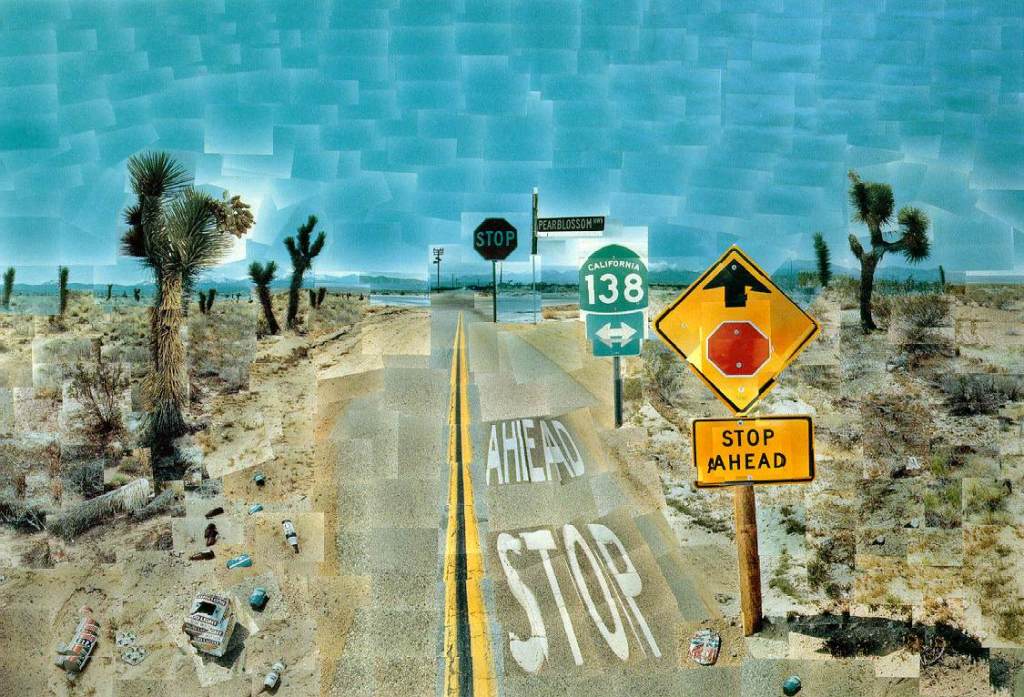

This is probably the most famous collage. It’s called ‘Pearblossom Highway’.

While looking at this artwork, a curious thing happens. You’re start by taking in the raw information in the scene: the tarmac, the expanse of blue sky, the roadsigns and cacti. But the more you look, the more you realise it doesn’t quite add up. This is not just a photo. Gradually you become aware of the act of looking itself; the different viewpoints you’d instinctively move into when looking at something

Hear David Hockney talk about Pearblossom Highway

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sD123svCFHQ

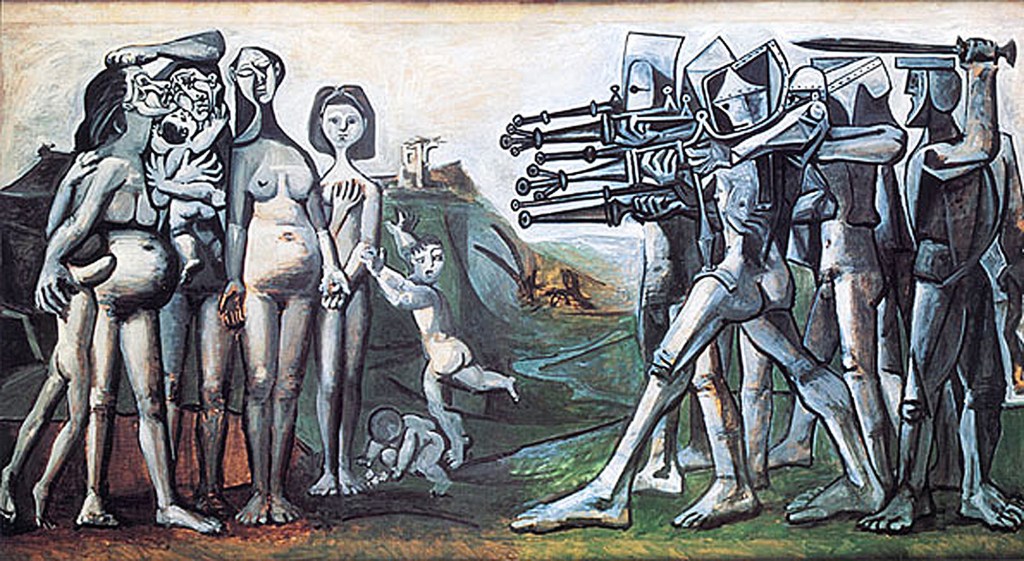

This honesty – the desire to reflect how we see the world – is one of my favourite things about Hockney. It’s also why Hockney champions Picasso, another artist that liked looking (and thinking about looking). Talking about Picasso’s painting ‘Massacre in Korea’ (see below), Hockney has said that he likes the painting because it presents the artist’s understanding of the war. Not just a set of realistic scenes from it (the kind a war photographer would take). It’s a different kind of truth.

This honesty makes its way into fashion too – and these are my favourite designers. They are the ones that don’t just want you to see clothes. They want you to see the act of wearing clothes. The garments we wear are loaded with information. Like a tuber root that has grown fat in soil, they are swollen with messages that our fertile imaginations have fed them.

Most of the time we are blind to them, because what they are telling us is what we expect (bride’s wear a white dress). But it’s a fake skin, one that looks natural, but is constructed and monitored by society’s rules.

The obvious hero of this approach to fashion is Martin Margiela and the work that came out of his Maison during the 1990s and beyond.

Here’s an absolute classic from that period – the blonde wig dress (below left).

Martin Margiela blonde wig dress

What I love about classic Margiela is the mix of seriousness and play. The clothes are beautifully made. So gorgeous are they, that you lean in to get a closer look. An unusual fastening is hidden between two layers of fabric. A silk lining brushes against the skin. A charismatic silhouette is created by the highest standards of tailoring. These are serious clothes… Yet, maybe the dress has been constructed by men’s bowties, ski gloves have become a bodywarmer or vintage leather evening gloves used to form a halter top. Such experiments lead to a variety of questions to bubble up in mind. Questions like: ‘Where did those gloves come from before they became a halter top?’ Who owned them?’ ‘Is that an appropriate thing to make clothes with?’ ‘What is an appropriate thing to make clothes with?’

The influence Martin Margiela has had on the next generation is enormous. Of the current crop of designers, Simon Porte Jacquemus is probably the most notorious and his Autumn/Winter 2015 collection showed him at his most conceptual.

Not really something you’d see worn down the King’s Road is it?

Taking the idea of ‘looking’ still further is this look (below left) from Jacquemus’ Spring/Summer 2016 season. Is this model actually wearing clothes, or is she wearing a clothes ‘signifier’? Questions like these conjure up a whole world of semiotic pain that would make Ferdinand de Saussure proud:

A look from Jacquemus’ Spring / Summer 2016 season

I for one find Jacquemus’ designs sometimes go a step to far. The reason why I like Hockney’s Pearblossom Highway, is because it teases and encourages you to linger. The most you stare at it, the more it plays games with you. What’s real? What’s not. In this regard, I much prefer Gucci Creative Director Alessandro Michele‘s approach to play, which draws on the tromp l’oeil designs of Elsa Schiaparelli, among others. But then again, who doesn’t these days?